In CNC machining, the quality of a component’s surface is just as important as its dimensional accuracy. Engineers often use the terms surface roughness and surface finish interchangeably, but the two concepts are not the same. Each describes a different aspect of the material surface, and understanding their distinctions is essential for proper design, manufacturing, inspection, and performance evaluation. This article explains what each term means, how they are measured, and why the difference matters in precision machining.

1. What Is Surface Roughness?

Surface roughness refers to the small, finely spaced irregularities that appear on a machined surface. These irregularities result from the cutting action of tools, the feed rate, machine vibrations, tool wear, and material behavior during machining. Roughness specifically focuses on the microscopic texture of a part.

Key Characteristics:

Describes small-scale surface deviations

Measured using parameters such as Ra, Rz, Ry

Strongly influenced by tool geometry, feed rate, and cutting speed

Directly affects friction, sealing capability, and part wear

Example: A surface with Ra 3.2 μm may be adequate for structural parts, while Ra 0.4 μm is required for sealing surfaces such as hydraulic components.

Surface roughness is often the most technical and quantifiable aspect of surface quality.

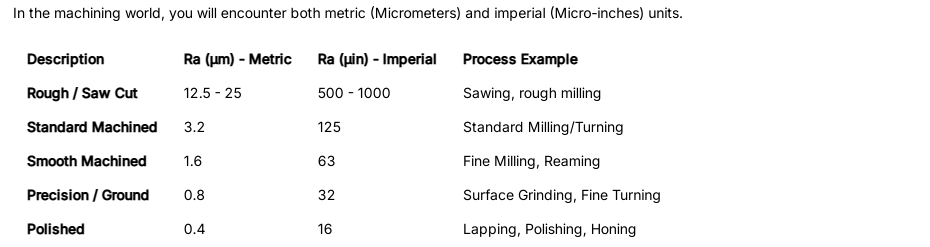

Summary Cheat Sheet: Common Conversions

2. What Is Surface Finish?

Surface finish is a broader term that includes surface roughness, but also encompasses surface waviness, lay patterns, machining marks, and any post-processing treatments. While roughness focuses on micro-scale texture, surface finish evaluates the overall look and functional quality of the surface.

Surface Finish Includes:

Surface roughness

Surface waviness (larger-scale deviations)

Lay (direction of tool marks or grain)

Surface treatments (polishing, grinding, coating, anodizing, plating)

In other words, surface finish reflects the total surface condition, combining both the microscopic texture and the general appearance.

Difference between Surface Roughness and Surface Finish

While the term “surface finish” encompasses three distinct components—waviness, lay, and roughness—it is roughness that engineers and machinists specify most frequently.

Surface Roughness is a quantitative metric. It measures the microscopic topography of a machined part, specifically calculating the vertical deviations between the highest peaks and the deepest valleys of the surface texture. Because this is a precise value, it requires the use of specialized metrology instruments to obtain accurate data.

Surface Finish, by comparison, is a qualitative assessment. It describes the general visual characteristic or “cosmetic look” of the part. Instead of numbers, surface finish is often categorized using subjective adjectives such as “glossy,” “matte,” “fine,” or “coarse.” Unlike roughness, which relies on hard data, surface finish is often based on human perception and visual inspection.

How is Surface Roughness Measured?

Quantifying surface roughness—essentially measuring the peaks and valleys on a part to see how far they deviate from a perfect form—requires specific metrology techniques. In the machining industry, we generally categorize these methods into five main approaches:

- Contact Profilometry (The Stylus Method)

This is the most standard method found in machine shops. It involves dragging a diamond-tipped stylus (probe) across the surface of the part.

How it works: As the stylus moves, it rides over the surface irregularities. The instrument records the vertical deflection of the probe and converts that movement into numerical data (such as Ra or Rz).

Best for: General quality control where physically touching the part is acceptable.

- Non-Contact Methods (Optical/Laser)

As the name implies, these techniques measure roughness without physically touching the workpiece.

How it works: These systems typically use laser scanners or white light interferometry. They project light onto the surface and analyze the reflection or scattering patterns to calculate the topography.

Best for: Soft plastics, delicate surface finishes, or parts where a stylus might leave a scratch mark.

- Image Analysis & Microscopy

This method relies on high-resolution cameras or specialized microscopes to capture 2D or 3D images of the surface.

How it works: The system uses software algorithms to analyze the visual data of the surface texture.

Best for: Parts with complex geometries, intricate details, or micro-features that are too small for a mechanical probe to access effectively.

- In-Process Monitoring

This is a modern approach used to measure roughness while the part is still inside the CNC machine.

How it works: Sensors or vision systems monitor the surface during the actual machining process.

Best for: High-volume production where stopping the machine for QC would kill efficiency. It provides real-time feedback, allowing operators to adjust parameters immediately if the finish starts to degrade.

- Comparison Techniques (Surface Comparators)

This is a manual, qualitative method often used for quick checks on the shop floor.

How it works: Machinists use a standard “comparator plate”—a set of metal samples with known roughness values (blasted, ground, turned, or milled). The operator visually compares the workpiece to the sample or uses a fingernail to compare the tactile feel.

Best for: Non-critical applications where a specific Ra number isn’t strictly required, but a general finish quality must be confirmed.

Why the Distinction Matters in CNC Machining

Precision Fit and Tolerance Control

Parts such as bearings, seals, pistons, and sliding components rely on consistent surface roughness to maintain friction levels and wear behavior. Engineers specify roughness to ensure functionality.

Aesthetic and Visual Quality

Consumer products, electronics housings, and decorative metal pieces often prioritize surface finish because appearance, reflectivity, and consistency matter.

Post-Processing Requirements

Understanding the difference helps determine whether additional finishing steps (polishing, sandblasting, anodizing) are required.

For example:

A machined aluminum part might meet roughness specs but still need anodizing for visual consistency.

A steel shaft might need grinding to reduce waviness even if roughness values seem acceptable.

Cost and Production Efficiency

Surface finish often requires additional manufacturing steps. A lower surface roughness often demands slower cutting speeds or secondary processes. Therefore, defining which requirement is actually needed prevents unnecessary cost.

Conclusion

Surface roughness and surface finish are related but not identical. Roughness refers to micro-scale texture measured numerically, while surface finish represents the entire surface condition, including appearance, waviness, and secondary treatments. Understanding both is crucial for precise engineering decisions, cost-effective machining strategies, and meeting functional and aesthetic expectations.

By differentiating the two, engineers and manufacturers can create better specifications, optimize machining processes, and ensure that CNC-machined parts meet both performance and visual requirements.